We’re Fighting Diabetes At Every Level: Hi-5!

- rrestoule1

- Nov 1, 2023

- 6 min read

Updated: Dec 2, 2023

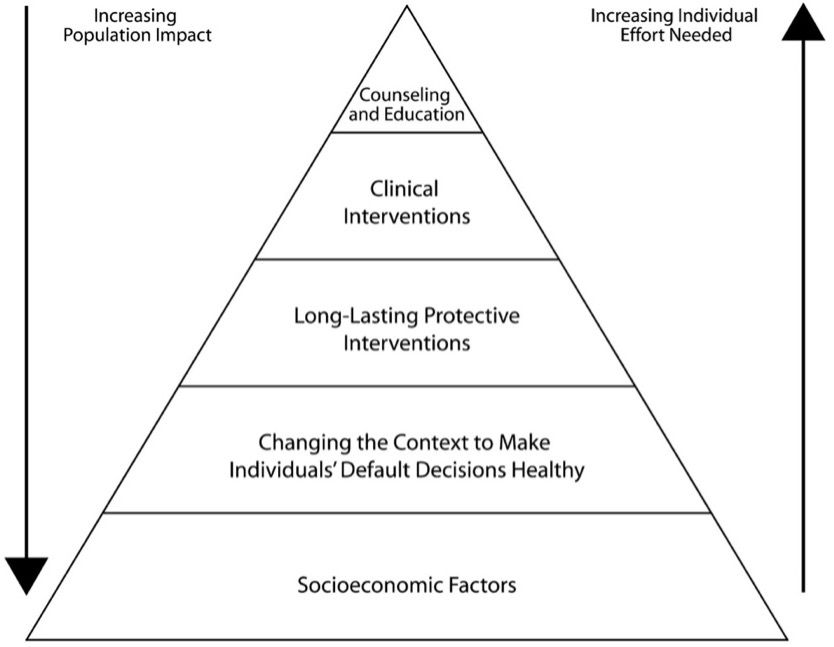

Settler colonialism has fostered a difficult living environment for the Indigenous peoples of Canada. Regardless, they remain resilient in the face of all adversities. Systemic inequities in healthcare are very modern examples of the impacts of settler-colonialism on daily Indigenous life. Today, communities are experiencing a disproportionate prevalence of Type-2 Diabetes (Dyck et al. 2010). Health authorities and communities are working hard to address the ongoing epidemic. The HI-5 method of public health improvement could be applied to this situation in order to generate very effective change. Based on Frieden’s Health Impact Pyramid, this multi-level model of health seeks to make changes by improving each part of the health care chain, from the individual to society as a whole.

The Indigenous population of Canada is disproportionately susceptible to many chronic diseases, one of the most prevalent being Type-2 Diabetes. According to the Canadian Diabetes Association, as of 2022, 17.2% of Indigenous peoples living on-reserve, 12.7% of Indigenous peoples living off-reserve, 4.7% of Inuit peoples, and 9.9% of Métis people live with Type-2 Diabetes, in comparison to only 5.0% of the general population (CDA 2023). In 2005, nearly 50% of Indigenous women over the age of 60 and approximately 40% of Indigenous men over the age of 60 were diagnosed with diabetes compared to 25% of non-Indigenous women and 20% of non-Indigenous men of the same age (Dyck et al. 2010). The catalyst to such a large prevalence of diabetes in Indigenous peoples are the many underdeveloped social determinants of health within communities. A lack of access to healthcare, low rates of education and income, and lack of healthy food choices in communities are all causes of this epidemic (Cheran et al. 2023). Research has determined that those of lower income and education levels are likely to develop diabetes at 2 to 4 times the rate of those with higher income and education levels (Hill et al. 2013). Many communities in Northern Ontario can only access healthy foods at heavily inflated prices and certain communities do not have access to potable running water. There is also a lack of health care and social services, meaning that community members do not have access to regularly scheduled care, healthy living programs, education about healthy habits, or extracurricular physical activity for children. It has been found that not only do poor social determinants of health lead to the accelerated development of diabetes, but that having diabetes impacts one’s social determinants of health in a negative manner as well (Hill et al. 2013). Diabetes, especially in Indigenous communities, is therefore a cyclically progressing disease, and must be addressed.

A multi-level approach to the diabetes epidemic would certainly create improvements within Indigenous communities. The Health Impact Pyramid is a useful public health intervention tool as it addresses issues at various levels (Frieden 2010), and considering the cyclical nature of diabetes, an aggressive approach such as this one is imperative. This multi-level approach divides public health interventions into five tiers. The lower tiers require less individual effort and have a population-wide impact (Frieden 2010). Interventions affect smaller population groups and require a higher individual effort going up into the tiers (Frieden 2010). The lowest tier on the pyramid addresses socioeconomic factors through improving social determinants of health for a given population (Frieden 2010). At this tier, developments in physical and social infrastructure must be made in order to improve the social and economic aspects of life for the general population (Frieden 2010). The second tier involves the modification of environments in order to generate healthier decisions from the public (Frieden 2010). The third tier addresses long-lasting protective interventions, which can be described as clinical methods that address the problem in one visit with long-term results (Frieden 2010). The fourth tier tackles clinical interventions, making consistent medical care equitable and accessible for all (Frieden 2010). Finally, the top tier addresses education and counselling for the general public to provide context and understanding of complex health issues (Frieden 2010). The top three tiers require commitment from an individual and are therefore more complex to implement. The HI-5 method, or Health Impact in 5 years is based upon Frieden’s Health Impact Pyramid, but it focuses on the bottom two tiers; improving socioeconomic factors and the modification of environments, as they impact the majority of the population while demanding minimal effort (CDC 2021). Applying the HI-5 multi-level approach to the ongoing diabetes epidemic within the Indigenous communities of Canada could lead to very effective changes.

The HI-5 public health intervention method focuses on the bottom two tiers of the health impact pyramid (CDC 2021). Confronting diabetes within Indigenous communities must therefore begin with addressing inequities in social determinants of health. In doing so, according to the HI-5 method, the problem will be addressed for the greatest amount of the population with the least amount of individual effort (Frieden 2010). Studies show that access to housing and healthy foods, and income and education levels are the primary social determinants of health influencing the development of diabetes (Hill et al. 2013). Due to the deeply complex implications of intergenerational traumas experienced by Indigenous peoples, pursuing post-graduate studies and acquiring a steady source of income can prove to be difficult. Creating environments where post-secondary education is more easily accessible, such as through online learning, could help alleviate this stressor. Additionally, ensuring access to childcare could offer further opportunities for individuals to seek employment. Then, Indigenous communities often only access healthy foods at incredibly inflated prices. If prices could be lowered on healthy items, Indigenous peoples could access healthier diets. Greenhouse and nursery programs could also be developed within communities, in order to give access to fruits and vegetables at reduced prices. Finally, ensuring that there is access to healthcare for Indigenous communities is an incredibly necessary element to the wellbeing of all peoples. Creating policy that could lead to these advancements in the social determinants of Indigenous health would certainly reduce the prevalence of diabetes within communities, as individuals would live generally healthier lives.

According to the CDC, the second step to the HI-5 method is to change the environment to make healthy pathways easier to choose (CDC 2021). In the case of diabetes in Indigenous communities, this would involve teaching both children and adults to live healthier lives through programming within the communities. The implementation of after-school programs that promote physical activity and healthy lifestyle choices would certainly instill positive habits in the children. Offering cooking and exercise classes for adults would facilitate healthy habits by removing the barrier of an individual having to research and teach themselves. By creating environments that promote healthy choices, the healthy choice is made easier for everyone. In doing so, choosing to live healthily will help to reduce rates of diabetes in Indigenous communities.

The disproportionate prevalence of diabetes within the Indigenous communities of Canada could certainly be resolved through the HI-5 method of public health intervention. Through focusing on mending inequities in the social determinants of health and creating environments that make healthy choices easier, the general population will benefit greatly and live healthier lifestyles. It is, of course, incredibly important to remain cognisant of Indigenous traditions and cultural practices when working in communities. It is therefore essential to apply the philosophy of Two-Eyed Seeing to the HI-5 method when addressing this public health matter. Using both Western and Indigenous knowledge and practices (Jeffery et al. 2021) is the only way to help reduce the incidence of diabetes in a culturally appropriate and ethical manner. Indigenous peoples abide by the 7 generations teaching; that ancestors 7 generations ago were thinking of us today, therefore one must make decisions while considering their lineage 7 generations from now. If these changes to Indigenous health policy can be made today, the children 7 generations from now will certainly not still be living in a diabetes epidemic.

References

CDC. (2021). HI-5: Health Impact In 5 Years. https://www.cdc.gov/policy/hi5/docs/hi5-overview-v6.pdf

Cheran, K., Murthy, C., Bornemann, E., Kamma, H., Alabbas, M., Elashahab, M., Abid, N.,

Manaye, S., & Venugopal, S. (2023). The Growing Epidemic of Diabetes Among the Indigenous Population of Canada: A Systematic Review. California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences & Psychology. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.36173

Canadian Diabetes Association [CDA]. (2023). Indigenous communities and diabetes. Retrieved 24 October 2023 from https://www.diabetes.ca/resources/tools---resources/indigenous-communities-and-diabetes

Dyck, R., Osgood, N., Lin, T., Gao, A., & Stang, M. (2010). Epidemiology of diabetes mellitus among First Nations and non-First Nations adults. CMAJ. 182(3): 249-256. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.090846

Frieden, T. (2010). A framework for public health action: the health impact pyramid. Am J Public Health. 100(4): 590-5 https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.185652

Jeffery, T., Kurtz, D., & Jones, C. (2021). Two-Eyed Seeing: Current approaches, and discussion of medical applications. BCMJ, 63(8), 321-325. https://bcmj.org/articles/two-eyed-seeing-current-approaches-and-discussion-medical-applications

Hill, J., Nielsen, M., & Fox, M. (2013). Understanding the Social Factors That Contribute to Diabetes: A Means to Informing Health Care and Social Policies for the Chronically Ill. The Permanente Journal. 17(2): 67-72 https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/12-099

Morrisseau, N. (n.d.) Sweat Lodge Ceremony Inside Turtle [Image]. https://www.tallengestore.com/products/sweatlodge-ceremony-inside-turtle-norval-morrisseau-contemporary-indigenous-art-painting-framed-prints

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada [TRCC]. (2015). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. PDF Document. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/trc/IR4-8-2015-eng.pdf

Comments